Scale theory

What is a scale? The easiest way to explain scales is as a collection of notes that because of a musical reason have been grouped together. The benefit of knowing scales in music is that you know how to orient yourself among notes. This will among other things give you a foundation for improvising – notes in a particular scale always sound good played together – and composing.

You don't need to read music to be able to learn scales, but it is always good to be acquainted with note reading. Neither do you have to know a lot of chords, but if you already know some chords the scales will be much easier to relate to and subsequently memorize. And by knowing scales you will be able to learn chord easier – chords derive from scales.

Fundamentals

A scale often consists of seven notes – this is the case of the Major and Minor scales. Scales repeat across octaves, which means the pattern of notes is the same regardless if you play a scale on the left, the middle or the right side of the keyboard.

On a full-scale piano, there is a total of 88 keys, but there are only twelve different tones which are repeated from low to high tones, from the base to the treble.

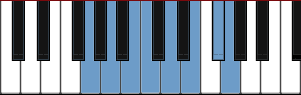

On the illustration above, you can see twelve tones that make one octave and these notes also form the Chromatic Scale. C# is sometimes written Db, D# is sometimes written Eb and so on. These are called enharmonic notes and how they are written depends on the key they belong to. The symbols after the letter (accidentals) are known as sharps and flats. C# is spelled “C sharp” and Db is spelled “D flat”. This is of course only theory and don't affect the sound, but is nevertheless good to know about.

We can use the G Major Scale as a first example:

The notes are G - A - B - C - D - E - F# - G.

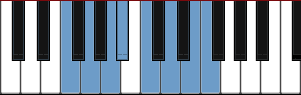

And now look at the F Major Scale:

The notes are F - G - A - Bb - C - D - E - F.

You have seen two different scales where sharps (#) and flats (b) are used. The rule that decides if the note is raised or lowered depends on the intervals between notes in the scale. In the examples above, F# is a raised F and Bb is a lowered B.

On some occasions you may observe two sharps or flats in adjunction to a described note in a piano score. These are called double-sharps and double-flats and need a theoretical explanation. If we take the key of D# as an example. This key includes both D# and D, but to make it functional in a score with a key signature it must be D# and C##; otherwise, you would be lured to play a D# instead of a D.

This affects how notes in scales are written out. For example, the C# Major Scale is correctly written: C#, D#, E#, F#, G#, A#, B#. Notice that B# is written instead of C. B# does not exist in reality and the note is played as a C. (There are many beginners using the site and mentions such as B# would clearly confuse some, therefore C is sometimes written instead of B# to avoid confusing whereas the formally correct notes are presented below in the scale overviews.)

See all double-sharps and double-flats listed in Appendix A.

How to Learn and Memorize Major Scales (theory lesson in PDF)

All lessons are available in the member area.

Changing keys

Music pieces are written in a certain key, like “Brandenburg Concerto No 1 in F Major” by J.S. Bach. It would be feasible to re-arrange this concerto to another key, like for example D Major. It would musically still be the same to a large extent, but the timbre would be different. See also The difference between scales and keys.

Relative and parallel keys

Certain major and minor scales are related by sharing the same notes. C Major and A Minor, for example, inherit the same notes (they differ by starting on different notes and therefore also differ in intervals). This relationship is named called relative keys, which is not the same as parallel keys. C Major and C Minor are an example of the latter.

Tonality

Most songs start and end with the same tone which tends to be the first note, the tonic, in the scale. Then you play notes from a scale, you can hear that the music seems to gravitate towards the first note, it is like some tension is left until you return to the first note. This phenomenon is called tonality.

Scale degrees

There is also something called scale degrees that refers to the relations of every particular note in the scale on a general basis. For example, the Major Scale can be written 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 and the Natural Minor can be written 1, 2, b3, 4, 5, b6, b7, referring to the degrees.

The piano scale degrees tool can be used as an interactive learning tool and dictionary.

Scale degrees can also be described by their functions and with Roman numerals as seen below:

Tonic (I): the first note of a scale which the scale is based upon, sometimes called the root.

Super tonic (II): second scale degree, one step above the tonic.

Mediant (III): third scale degree with a position halfway between the tonic and the dominant.

Subdominant (IV): fourth scale degree, a fifth below the tonic and next to the dominant.

Dominant (V): fifth scale degree.

Submediant (VI): sixth scale degree and sometimes called supermediant.

Subtonic (VII): seventh scale degree which is also referred to as leading tone because it musically “leads” back to the tonic by a half step interval. Whereas the leading tone applies in major scales and harmonic/melodic minor does the subtonic (bVII)m with flatted seventh appear in the Natural Minor.

Whereas seven-note scales include all of these scale degrees, five-note scales lack two of them, which affects the sound character.

Why should you learn these terms? One great thing about knowing them is that you can have a better understanding of scales and chords in an abstract way. For one of many reasons, this will help you transposing music to another key and give you hints while you are composing music.

To give a concrete example: in blues you frequently use the tonic (I), subdominant (IV) and the dominant (V) in regard of chord progressions. By knowing this theoretical relationship, you can better understand how to play blues in different keys.

Steps and intervals

A way to describe the structure of a scale is by steps, which refer to the distance between notes. The most used terms are half steps and whole steps. Between C and C# there is one half step, and between C and D there is one whole step.

In the scale overviews on this site you will also see “Semitones” (equivalent to half steps) and “formulas” used to describe the scales. It is mainly the same thing only described in a different way. For the Major Scale this will look like: 2 - 2 - 1 - 2 - 2 - 2 - 1 (semitones) or Whole, Whole, Half, Whole, Whole, Whole, Half (formula).

See all steps listed in Appendix B.

Closely related to steps are intervals, which is explained in a separate section.

Order

When a scale is presented, the tones are ordered from the root note followed by the tones that comes in order. This doesn't mean that scales should be played in a certain order. When practicing, yes, when improvising, no.

Since the tones in scales are not played simultaneously where is no need for inversions of piano scales as sometimes is the case concerning chords.

Tones and notes

The words tones and notes are sometimes treated as synonyms, but they can be distinguished. The sound in music is made from tones. A note rather describes the tone in matters of pitch and duration. Notes are used as symbols in sheet music for describing how the music should be played in measurable ways, such as a whole note being played be the C key on the fifth octave, a quarter note being played on the E key in the sixth octave.

Related to tones and notes are pitch, duration and dynamics. Pitch describes the highness or lowness of a tone, duration describes the length of a tone and dynamics are the loudness or softness of a tone.

Continue and learn more about basic piano terms

Appendix A

All double-sharps and double-flats and the notes they represent.

C##: the same as D natural.

D##: the same as E.

E#: the same as F.

F##: the same as G.

G##: the same as A.

A##: the same as B.

B#: the same as C.

Cb: the same as B.

Dbb: the same as C.

Ebb: the same as D.

Fb: the same as E.

Gbb: the same as F.

Abb: the same as G.

Bbb: the same as A.

Appendix B

All steps and the distances in semitones (Semitones) they refer to.

Half: one step.

Whole: two steps.

Whole and a half: three steps.

Quadra-step: four steps.