Compose music

In this introduction about composing music, you will learn about melody and harmony concepts such as chord tones, passing tones and landing tones.

A song typically consists some main components, in which harmony, melody and lyrics (if it is not instrumental) is present.

Melody

The melody is often the most distinct part of a musical work. It is the melody you often remember from a song and maybe find yourself whistle later. A melody can be created from a small musical idea, sometimes referred to as a motif. As an example, Beethoven’s "Symphony No. 5" begins with a short, recognizable motif: "da-da-da-dum".

Chord tones and passing tones

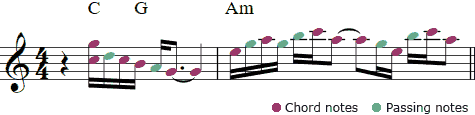

To choose which notes to play for the melody, a central concept is to match the chords that are played. Tones that are included in the chord are called chord tones and notes that are between the chord notes in the related scale are called passing tones (e.g. D is a passing tone between C and E). The chord tones are strong melody notes and will sound great to play over matching chords. Passing tones are also useful when variation is needed.

Below is an example with two bars showing the melody that is played with a piano over an arrangement with other instruments. Look at the notes and you can see how the notes of the melody correspond with the chords played. Listen to the audio to hear the melody (solo piano) together with the harmony (several instruments).

One thing to notice in the picture above is that chord notes are chosen in every occasion directly when a new chord is played. These are called landing notes. Although, this is one of many methods, it is a common approach in playing melodies over chords.

Repetition

It can be enough with one or two phrases, each including one or two bars, as the foundation of a melody. It is a common mistake to keep on introducing new melodic ideas over and over. It is often better, and easier as well, to repeat the melodic themes with slighter variance, which makes the melody coherent.

The repetition should not be exact and too much repetition without variation can make it boring for the listener. The common AABA structure demonstrate this:

| Part | Theme | Action |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | Introducing a melodic theme. |

| 2 | A | Almost the same as part one. |

| 3 | B | Introducing something new, for example a chorus. |

| 4 | A | Re-introducing 1st or 2nd part. |

Other ways to repeat and deviate on the same theme are the following:

- Repeat the melody, but change the harmony.

- Repeat, or almost repeat the melody, but change the key.

- Change the dynamics, for example playing a part softer with another expression.

Study famous classical music pieces and you will notice that there are almost always repetitious elements in some degree.

Retrograde

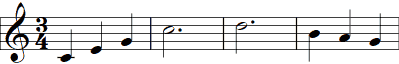

One of many techniques used by composers to expand melodies is a retrograde. A retrograde is a turning of a series of notes in opposite direction. An example can be found in the Gaelic hymn “Morning has Broken”:

This example is not fully symmetrical, but it still illustrates a retrograde. After the fourth tone, the ascending figure turns to a reversed descending figure. (This example is partly taken out of context to illustrate a retrograde in a simple way. The melodic idea actually involves the five and not the four first notes in the sheet music excerpt. And the response (the retrograde) is involving another note which has been left out in the example.)

Inversion

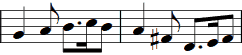

Another similar technique is the inversion. An inversion involves turning a series of notes so that ascending intervals become descending and vice versa. An example can be found in the traditional song “Greensleeves”:

The figure in the first bar is mirrored (not fully symmetrical though) in the second bar. (This example is also partly taken out of context to illustrate an inversion in a simple way. The melodic motif is involving more notes than showed in the sheet music excerpt.)

If you need blank sheet music manuscripts, go to Appendix.

Harmony

Harmony in music refers to how multiple notes interact when played together, often both reinforcing the melody and contributing to the mood or atmosphere of the song. A concrete example of harmony in music can be an instrument accompanying a singer. Whatever the ingredients are the harmony is collaborating with the melody. Whereas the melody in sequence (horizontal), the harmony is played with many notes together (vertical).

Combine harmony and melody

The order in which harmony and melody are created can vary among composers. The art of combining harmony and melody is done with talent, experience and some guidelines. This article cannot offer talent or experience, but it can give you some basic guidelines.

Two fundamental elements in composing music are scales and chords. When creating a piece of music, the knowledge of scales is indeed helpful. Maybe you are sitting in front of a piano without a clue which keys to press down for making it sound alright?

The easiest way to start composing on the piano? Just play exclusively on the white keys! Obviously, this cant be done in all keys (the white keys are matching C Major or A Minor), but it can serve as a beginning.

Doing this, you are playing in the key of C Major, and therefore you do not hear any dissonance. You can use the white keys for both harmony and melody. Use your left hand for chords (this site focuses mainly on scales, if you want to discover more about chords use your search engine or visit Pianochord.org), and your right hand for the single notes.

Of course, this is a simple approach to composing, but it is a start.

The song structure and related areas

When you are composing a song, it is often enough to stay in one or two keys throughout the song. A typical song starts in one key and stays in it, or, changes key somewhere in the song and most often return to the original key before the end.

In popular music, a typical song structure can be something like this:

- Intro

- Verse

- Chorus

- Verse

- Chorus

- Bridge

- Verse

- Chorus

- Outro

The verses approximately consist of three to six lines and usually with different lyrics. The choruses tend to use fewer lines and often repeats the same lyrics.

So, you got a melody and need some harmony?

There is more than one way to create harmony; two common ways are counterpoints or chords. We are taking the easiest route and choose chords.

Once again, there is more than one way to add chords to a melody. Since this is only an introduction in music composition we are satisfied with two rules: 1) add chords in which the second or third note is the same as the melody note; 2) don’t add chords to every melody note, one or two in every bar are often advisable.

Concerning the motion: the harmony can be parallel or contrary to the melody line. To think of the motion in this way can be helpful.

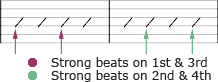

If we have a song in 4/4 time, which is the most common, chord changes often occur on the first or/and third beat in the bars. The first and third beat are also often most accented. But in rock and jazz, in particular, the strong beats can also lay on the second and fourth beat, so-called off beats.

Tonic, subdominant and dominant

Many songs include only three chords, and they are often the tonic, the subdominant and the dominant (see Theory - Scale Degrees for further information). The dominant chord has normally a minor seventh and it resolves well into the tonic. An example could look like C - F - G7 - C.

Ending it

When you reach the end of the song, a common method is to shorten the intervals between chords. This accomplishes a breaking effect. The name often used for a chord sequence at the end of a phrase or song is cadence. One example of a cadence in C Major: C - G - F - C. A cadence in A Minor could be: Am - Dm - E7 - Am.

The Circle of fifths

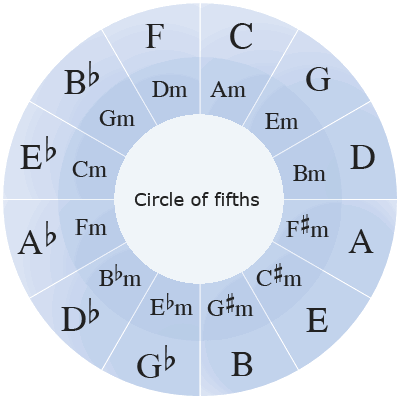

When composing music, it serves you to have a visualization of the relationship between harmonic distance, including aspects of chords and scales.

When composing music, it serves you to have a visualization of the relationship between harmonic distance, including aspects of chords and scales.

A common visual way to present this is by the Circle of fifths. It is called so because every note is a perfect fifth away from the next, going clockwise (turning counterclockwise will instead result in fourth intervals). A composer knows that ,for example, a D7 chord resolves into G, a G7 chord resolves to C and so on.

The circle also shows the relative keys (major and minor). A Minor is, for example, relative to C Major. This means that you can play the same notes in A Minor as in C Major, but starting from the note of A (or expressed a little differently, use the A note as the tonic center). By doing so you get a somewhat melancholy sound. Compare major and minor scales and you will notice the contrasts and relationships.

The schematic circle could instead be stretched out as horizontal series. The outer and inner regions will be:

C - G - D - A - E - B - Gb - Db - Ab - Eb - Bb - F

and

Am - Em - Bm - F#m - C#m - G#m - Ebm - Bbm - Fm - Cm - Gm - Dm

Another way to use the circle as a reference is that you can use three adjacent “slices” and the major and minor chords will sound great together. For example, Bb and Gm plus F and Dm plus C and Am, will work nice together.

Appendix

Blank sheet music for piano with some variations of key and time signatures. Click on the links to open sheet music manuscript papers in PDF-files.

Blank sheet: no signatures, clefs or bar lines

Blank sheet: no signatures or clefs

Blank sheet: 4/4, no key signature

Blank sheet: 3/4, no key signature

Blank sheet: time signature cut common time

Blank sheet: 4/4, G major

Blank sheet: 4/4, D major

Blank sheet: 4/4, F major